That's What Michael Scott Said - Text Prediction using Recurrent Neural Networks

Hello! In this post I am excited to share with you a text generator that I created using recurrent neural networks. I was lucky enough to find out that there is a data set containing every line ever from The Office, and my goal with this analysis is to build a text generator that will predict what Michael Scott might say next!

Neural Networks

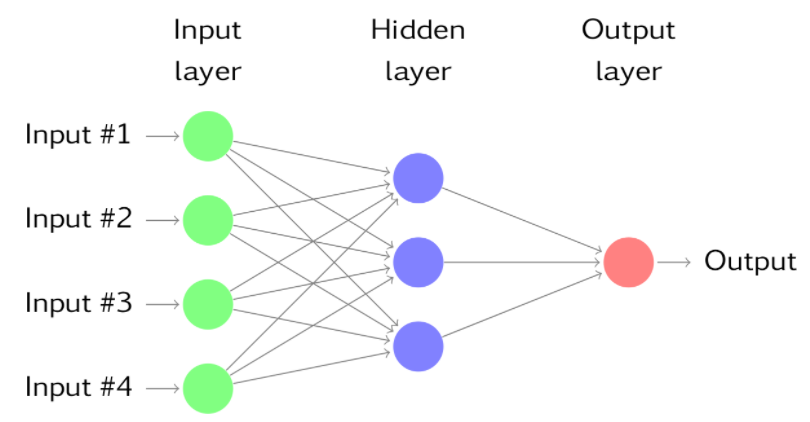

In Machine Learning, neural networks are a form of Deep Learning designed to loosely mirror the human brain. Neural networks aid in tasks like clustering and classification, as they are good at identifying patterns within data. The general make-up of a neural network can be described as three layers:

Input Layer: This is the layer that receives the data and passes it on.

Output Layer: The result of this layer is the forecast, and it depends on the type of model that you are building. For example, if you are classifying handwriting samples to determine which letter is being used, then your output layer would consist of 26 nodes, one for each letter of the alphabet.

Hidden Layer: The hidden layer is somewhat of a black box mechanism. It lies between the input and output layers, applying transformations to the inputs before feeding those out. Within this layer, the inputs are transformed, weighted by significance, and adjusted until the model fits the data. The neural network is considered “deep” if it contains more than one hidden layer.

Feed-Forward Neural Networks

The image above displays what is called a feed-forward neural network. In a feed-forward network, each layer receives inputs from the previous layer, and then feeds the output to the next layer. This is the simplest type of neural network, as information always moves in one direction.

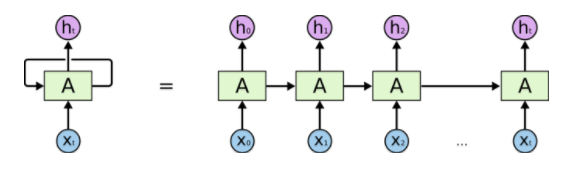

Recurrent Neural Networks

A recurrent neural network (RNN) is more dynamic, as it can use its internal state, or memory, to understand and process sequences of inputs. In the feed-forward network above, we assume that all inputs and outputs are independent of each other, whereas a recurrent neural network takes into account any information that has already been calculated so far, and allows it to persist. They are designed to recognize patterns in sequences of data, such as text and speech. An everyday example of an RNN is your phone’s word completion/suggestion feature. With each letter you type, the network is evaluating the entire sequence of letters and then suggesting (predicting) the completion of the word and evaluating the sentence to predict which word you might want to use next.

The cyclic nature of an RNN is portrayed in the image below:

The specific type of recurrent neural network that we are going to use is called a Long Short Term Memory network, or LSTM, which is superior for cases where long-term dependency on information is important, such as text prediction.

Let’s Model

To implement our recurrent neural network, we will be using the keras package for R. If you have never used this package, you will also need to install Anaconda and then run install_keras() after loading the library.

The Data

library(readr)

library(stringr)

library(tidyverse)

library(tokenizers)

library(keras)

office <- read.csv("the-office.csv")You can see below that this data set contains information about the season, epidsode, and speaker of each line, as well as the complete lines themselves.

str(office)## 'data.frame': 59909 obs. of 7 variables:

## $ id : int 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ...

## $ season : int 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ episode : int 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ scene : int 1 1 1 1 1 2 3 3 3 3 ...

## $ line_text: chr "All right Jim. Your quarterlies look very good. How are things at the library?" "Oh, I told you. I couldn't close it. So..." "So you've come to the master for guidance? Is this what you're saying, grasshopper?" "Actually, you called me in here, but yeah." ...

## $ speaker : Factor w/ 797 levels "(Pam's mom) Heleen",..: 468 359 468 359 468 468 468 552 468 552 ...

## $ deleted : logi FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE ...head(office$line_text, n = 3)## [1] "All right Jim. Your quarterlies look very good. How are things at the library?"

## [2] "Oh, I told you. I couldn't close it. So..."

## [3] "So you've come to the master for guidance? Is this what you're saying, grasshopper?"To save some computational complexity, we are only going to use one season for this analysis. I decided to use season 2, and I also chose to exclude any deleted scenes.

michael <- office %>%

filter(speaker == "Michael"

& deleted == "FALSE"

& season == 2)

lines <- michael$line_textNow we have a list that contains all of Michael’s lines from season 2.

head(lines, n = 3)## [1] "Tonight is the Dundies, the annual employee awards night here at Dunder Mifflin. [holds up a trophy of a business man] And this is everybody's favorite day. Everybody looks forward to it, because, you know, a lot of the people here don't get trophies, very often. Like Meredith or Kevin, I mean, who's gonna give Kevin an award? Dunkin' Donuts? Plus, bonus, it's really, really funny. So I, you know, an employee will go home, and he'll tell his neighbor, 'Hey, did you get an award?' And the neighbor will say, 'No man. I mean, I slave all day and nobody notices me.' Next thing you know, employee smells something terrible coming from neighbor's house. Neighbor's hanged himself due to lack of recognition. So..."

## [2] "[in a Fat Albert voice] Hey hey hey! It's Fat Halpert."

## [3] "[in Fat Albert voice] Fat Halpert. [in normal voice] Jim Halpert."Prep

There are a lot of stage directions included within the text, and I want to get rid of those since they are not part of the actual speaker lines. We can do this by removing any text that appears within square brackets. (It may be interesting to build a model that includes these stage directions to see if the network can script a scene).

We want our data to be in the form of a vector where each element is a single character.

lines_sub <- gsub("\\[[^\\]+\\]", "", lines)

chars <- lines_sub %>%

str_to_lower() %>%

str_c(collapse = "\n") %>%

tokenize_characters(strip_non_alphanum = FALSE, simplify = TRUE)

head(chars, n = 20)## [1] "t" "o" "n" "i" "g" "h" "t" " " "i" "s" " " "t" "h" "e" " " "d" "u"

## [18] "n" "d" "i"We also need a separate vector that contains only the unique character elements from above. We will use this as an index reference for the character elements.

chars_unique <- chars %>%

unlist %>%

unique() %>%

sort()

head(chars_unique, n = 20)## [1] "'" "-" " " "\n" "!" "$" "%" "," "." "/" ":" ";" "?" "0"

## [15] "1" "2" "3" "4" "5" "8"## [1] "total characters: 47"We are going to create a data set that contains sequences of characters with a length equal to the average length of a Michael Scott line. This data set will contain multiple list elements, each having [1] the sequence of characters of average line length and [2] the character that immediately follows that sequence. These sequences will overlap one another to ensure we have thorough representation of all potential sequences. This data set will help us build our predictor and target vectors for training the model.

seq_len <- round(mean(nchar(lines)))

dataset <- map(

seq(1, length(chars) - seq_len - 1, by = 3),

~list(sequence = chars[.x:(.x + seq_len - 1)], next_char = chars[.x + seq_len])

)

dataset <- transpose(dataset)Since we are using the keras package to train our model, we need our data to be an array of form (number of sequences, length of sequence, number of features). We can first create two empty arrays to pre-allocate the space, and then fill in the first element using a for loop.

x <- array(0, dim = c(length(dataset$sequence), seq_len, length(chars_unique)))

y <- array(0, dim = c(length(dataset$sequence), length(chars_unique)))for(i in 1:length(dataset$sequence)){

x[i,,] <- sapply(chars_unique, function(x){

as.integer(x == dataset$sequence[[i]])

})

y[i,] <- as.integer(chars_unique == dataset$next_char[[i]])

}Model

Now our data is ready for modeling! As stated above, we are going to imlement an LSTM model. We will add this layer to our sequential model, defining the dimensions of the input shape similar to our x array created above. We will use softmax as our activation layer, which will cause our resulting predictions to sum to 1. We will use the RMSProp optimizer, which is usually a good choice for recurrent neural networks, with a learning rate of 0.01 (you can adjust this parameter as you see fit).

I had to run this model overnight using 200 epochs, so if you are crunched for time you might want to try lowering that value (this will, of course, alter the performance/results of your model).

model <- keras_model_sequential()

model %>%

layer_lstm(128, input_shape = c(seq_len, length(chars_unique))) %>%

layer_dense(length(chars_unique)) %>%

layer_activation("softmax")

optimizer <- optimizer_rmsprop(lr = 0.01)

model %>% compile(

loss = "categorical_crossentropy",

optimizer = optimizer

)

history <- model %>% fit(

x, y,

batch_size = 128,

epochs = 200

)Now that we have built the model we can see what type of sentences it will generate!

I am asking it to generate 1000 sequences of length 200, and each of these will be initialized with a randomly chosen sequence from our data. As each new character is predicted and added to the sequence, we will feed those sequences back into the model until we have generated 200 new characters.

predicted <- NULL

for (j in 1:1000) {

start_index <- sample(1:(length(chars) - seq_len), size = 1)

sequence <- chars[start_index:(start_index + seq_len - 1)]

predicted[[j]] <- ""

init <- NULL

for(i in 1:200) {

init <- sapply(chars_unique, function(z){

as.integer(z == sequence)

})

init <- array_reshape(init, c(1, dim(init)))

preds <- predict(model, init)

next_index <- preds %>% which.max()

next_char <- chars_unique[next_index]

predicted[[j]] <- str_c(predicted[[j]], next_char, collapse = "")

sequence <- c(sequence[-1], next_char)

}

print(j)

}I have included a few snippets from the model results below. In general, the model did decently well at building English words. It was also able to correctly use an apostrophe and form sentences with punctuation.

“you know what? i am going to be atting place. so i drrrupe, i win.”

“that’s her the day. ok? you know? why don’t you, ah, what is that i go sight.”

The model also recognized Michael’s propensity to reference other characters, and the output showed a lot of references to Dwight, Jim, Pam, and Jan.

“because i did dwight be fearing from well get hows to think you wiftso comestion to pam?”

“show yaaaal… come on, jan, a good work.”

Of course, there is a lot of output that did not make much sense at all. I am still very new to deep learning, and this was only my first attempt at building a LSTM network. I hope to spend more time tuning the various parameters and performing model validation and evaluation to hopefully build a model that can more accurately complete these lines.

Conclusion

We have seen that keras and LSTM networks can help us build a simple text generator, however there is clearly room for improvement. I hope that this walkthrough has given you a solid introduction to understanding recurrent neural networks and how we can implement them in R, and I wish you the best with your machine learning endeavors!